The Ballard Story

By Gibbon Simmons, Conservation Delivery Specialist, KS

Responding to my previous article, Officer Trevor Ballard, of Smithville, Missouri, shared many memories of upland bird hunting north central Kansas. Ballard grew up on the northside of Kansas City, MO. His best friends, the Elder boys, invited him to go pheasant hunting. With permission from his father Charles Ballard, he joined them, and he was hooked!

The Elder and Ballard families have been friends for generations back to when both families lived in Manhattan. The families remained friends after moving away. Ballard’s friends belonged to a man named Larry Elder. Recognizing the passion in young Ballard, Larry Elder became his mentor in the ways of bird hunting. “My old man never hunted unless I begged him. Hunting and fishing weren’t his thing. My dad was into athletics and sports, especially K-State athletics. He was a good dad, he let me go hunting and he went with me because I wanted to,” said Officer Ballard.

Chasing his new obsession, young Ballard would ride his bike for a couple of miles to hunt as often as he could at the edge of town. He began working for local farmers with prime upland habitat. A deal was always struck between young Ballard and the farmer owning the habitat in question. Young Ballard pledged his service to the farmer and in return the farmer permitted Ballard to hunt the property. A win-win deal if there ever was.

One hunt, the crew loaded up in Larry Elder’s red pickup truck. They put Charles Ballard’s blue camper shell over the bed. The result was, “a real Frankenstein Rig” chuckled Ballard. Nevertheless, westbound on Highway 36, the two families began an adventure to Smith County Kansas.

“I began my pheasant hunting career in Smith County in 1990 at the ripe old age of eleven. Killed my first rooster out there” beamed Officer Ballard. “We hunted CRP ground north of Smith Center, KS, close to the Nebraska border.” Larry Elder’s Uncle Willard owned the land they hunted on in Smith County.

One hunt, the Elder and Ballard crew were on CRP land. There was a bush in a ditch on the side of the road. They crept close, staring at and studying this bush. Then. . . one, two, three, four, five, six, seven, eight, nine. Nine roosters flew out of that bush! Quickly they unloaded their guns at the birds. “We maybe only hit a few but we’ll never forget the Clown Car Bush,” said Ballard.

Another time when Ballard was about thirteen or fourteen years old, he had to call a timeout during a pheasant hunt. When nature calls, you must answer. But as we all know, nature itself does not abide by any timeouts called by a hunter. Roosters burst forth from the ground! Scrambling to shoulder his gun (though his pants were down to his ankles), young Ballard focused, BOOM. . . BOOM. . . dead bird. Admit it, you’ve tried it too; though, very few of us hit in this situation.

Fond memories, and from Officer Ballard’s point of view, though pheasant hunting in north central Kansas is now “more or less a memory.” “Back then there were still plenty of buffer strips and CRP. Farming practices have changed a great deal.”

I had to explore Officer Ballard’s explanations as to why pheasant hunting in north central Kansas isn’t like it used to be. Which brought me to the National Wild Pheasant Plan. Wildlife conservationists endlessly beat the drum “more habitat, more wildlife", and this is true without question. But there are two domains that remain uncertain for pheasants. One, “although the birds' needs are the same as they ever were, the agricultural environments they inhabit are constantly changing due to emerging market forces, technologies, and farm policies,”(National Wild Pheasant Plan). Two, “simply knowing the pheasant's basic needs has not prevented their decline in many areas. Effective pheasant management is not just about biology, but includes aspects of the social sciences, as well. Social factors influence hunter activity (and hence license revenues), farming and ranching decisions, and policymaking, which in turn critically impact the manager's ability to work with landowners in providing habitat,” (National Wild Pheasant Plan).

Officer Ballard hit the mark when asked what a reverse course looked like. “Attitudes in farming needs to change first. Second, habitat, more habitat.” He noted the social and biological aspects of managing pheasant populations.

Next, I began to research the Conservation Reserve Program (CRP). Here is a brief lesson on CRP: it is a voluntary, incentive-based program administered by USDA Farm Service Agency. Agricultural producers are encouraged to enroll environmentally sensitive land (highly erodible land) on a long-term basis (ten to fifteen years). Once enrolled the land is used for conservation efforts. Native grasses and forbs are planted to control soil erosion, improve water quality and develop wildlife habitat, which is huge for upland birds. CRP participants are paid for their conservation efforts annually.

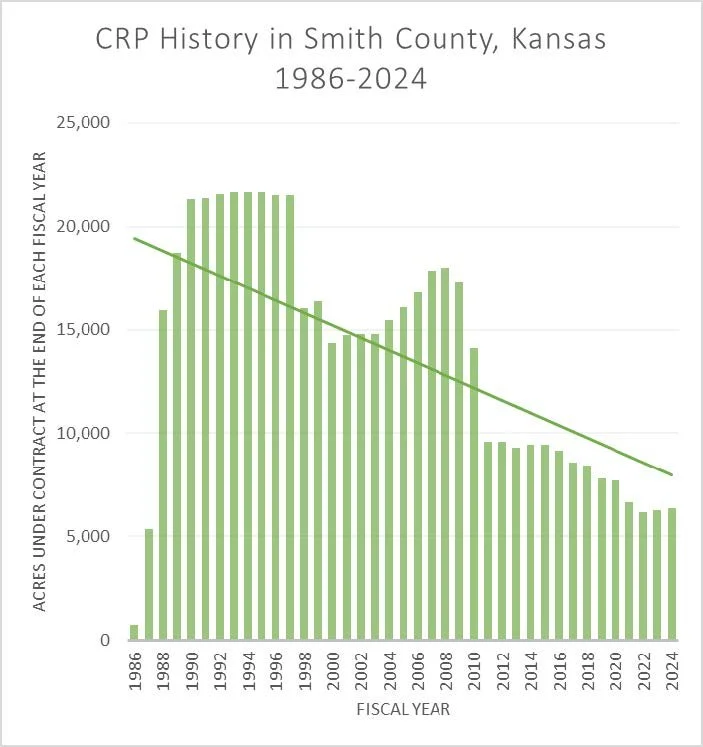

Nationally, the total acres enrolled in CRP in 2024 falls 10.4 million acres short of the 35 million acres enrolled in the early 1990s (National CRP Statistics) . Are these statistics relevant to pheasant hunting in north central Kansas? I called the USDA Farm Service Agency (FSA) in Smith County Kansas to dig a little deeper. Here is what I found…

In 1990 when Officer Ballard went on his first pheasant hunt in Smith County, KS there were 21,344 acres enrolled in CRP, providing wildlife habitat for pheasants, quail, and other wildlife. In 2024 there were just 6,350 acres enrolled in CRP. That’s nearly 15,000 acres short!

Remember the old days when upland birds were plentiful? The birds’ needs haven’t changed, but the landscape they depend on has changed and continues to change. “We’re seeing a perfect storm against pheasants. When you’re living it, it’s hard to see that it’s the golden days. CRP is not the smoking gun or the silver bullet,” said Ballard sadly.

Finally, I asked Officer Ballard what would bring him back to Smith County. He answered, “Nostalgia. One more hunt like the old days.”

So many of us relate to this story and others like it. Our common ground is the ground we hunt on, work on, and live on. If you relate to this story, take action for the conservation of upland habitat. The Great Plains Grasslands are collapsing. It will take every one of us to confront the threats we face.

Do you have stories about the golden days of pheasant hunting in north central Kansas that you would like to share? Please contact me at dsimmons@pheasantsforever.org or call me (785) 515-8398.